The waxwork is a new medium of Buddhist materiality that now coexists with the metal statue, the photograph, and the painted scroll in the Tibetan cultural sphere. It is usually departed Buddhist masters who are immortalized as wax effigies. The hyperrealistic aesthetics extends their presence among devotees since wax can be formed and colored to look exactly like the living person. Tibetan waxworks are particularly fascinating in relation to the Buddhist sacred. My research explores different Tibetan waxworks (in Kham and Chengdu in China) and how people discover, desire, produce, acquire, and engage with waxworks of the living and the dead – all of which are topics for future articles. In this article, I introduce the waxwork as a new medium of Buddhist materiality, and I present one assemblage of a deceased religious authority and its living maker.

What are waxworks?

Before the early nineteenth century, all wax was beeswax. Nowadays, when we talk about wax, we often do not mean beeswax, but something similar, usually chemically produced, such as silicone, plastic, and acrylic. And what is known today as wax effigies signify “…statues simulating human form, whether or not they are made of wax.” (Bloom 2003: 266). I will consequentially talk about wax and waxworks, following the popular naming of hyperrealistic statues that resemble living beings.

Historically (and outside of the Tibetan context), wax has been used to make votive tablets and molds for bronze casting, and later to create incredibly realistic and evocative wax effigies. There are four main forms of wax effigies, one being the votive ceroplastic such as Catholic body relics (Napolitano 2017), and the other three are secular forms; the modern wax doll that looks like an infant (Wallace 2014), the anatomical model used for scientific research and pedagogical purposes (Ballestriero 2009), and the popular waxwork that was commercially exploited, most famously by Madame Tussaud (Kornmeier 2008).

Waxworks have a long history in Europe, where they have become part of popular culture. Nonetheless, I have not visited any of the world’s twenty-four Madame Tussauds wax museums. I never understood the desire to be in the same room as those eerie mimetic copies of the living and the dead that looked alive but were arrested in disturbing stillness. I have to admit, however, that they have a powerful and compelling force because they look so lively. Wax is used to create a strikingly realistic mimetic likeness in artifacts – in terms of form (it is malleable), coloring (it easily absorbs paint), and light (it holds light, making models look alive) (Ballestriero 2009 and Napolitano 2017).

Before waxworks came to Kham in the 2010s, I am not aware of any uses of wax in Tibet except to craft molds for casting. Nowadays, one can see Tibetan waxworks in museum displays, for example in Litang Khampa Museum (est. 2019), and there are the wax models of Buddhist authorities installed in Tibetan monasteries in Kham. I also know of two statues of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, one in Nepal and one in Bhutan, and a statue of the Sixteenth Karmapa.

Wuhouci waxworks

The first Tibetan wax statue that I saw was sitting in a showroom in Wuhouci, the Tibetan market in downtown Chengdu that is the center for trade with Tibetan Buddhist goods. The shop was run by a Tibetan artisan monk from Kham who had been operating a workshop for religious objects for several years. It was a seated, clothed wax statue. In its lap sat a donation box with a hand-written message saying, lag pas ma reg rogs/ (“Do not touch”). I took its picture in 2015 (Figure 2). The statue was of a locally famous tertön (Tib. gter ston) in Kham, a Nyingma adept who was considered a discoverer of hidden teachings.

Like other well-executed waxworks, this model had hyperrealistic features and a glow that made him look alive. Realistic images of beloved masters – dead or alive – are not unusual in the Tibetan cultural sphere. Photographs of Buddhist authorities are commonly seen on Tibetan home shrines and also in temples where they are placed on the seat of the master when he is not present. Additionally, there exist painted scrolls depicting departed or current Buddhist masters arranged according to traditional iconography, coloring, and mounting but with realistic faces. Nowadays, Chinese and Tibetan factories also 3D-print small statues using different materials: metals, wax, and silicon statues of renowned Buddhist masters that have recognizable features – though the latter is not as popular as the traditional metal statues. When wax is the material used to make life-size statues, the representation of one’s guru is brought to a whole new level.

My preliminary research into Tibetan waxworks in and around Chengdu reveals that producing and displaying wax effigies of Tibetan Buddhist masters is a new phenomenon. When customers started to ask for waxworks in Wuhouci, most of the businessmen established there – who were already producing Buddhist statues and had the required understanding of iconography and design – did not have access to technology and resources to get into the waxwork business. It was only in 2018–2020 that the waxwork market started to bloom in Wuhouci. Still, the waxwork market is comparatively small, so manufacturers are few.

One only needs to bring money and a photograph of one’s beloved guru to have him made in wax. Only a few workshops are able to make wax models of Buddhist masters from scratch because they do not have the skills to create new models using 3D printing and clay model making. A new statue (i.e., not reproduced from already existing models) is sold for 50,000–200,000 Chinese Yuan (6,400–25,600 Euro). Most waxwork orders, however, are for two standard models of a seated Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok. He was the charismatic Buddhist leader and monastic founder of Larung Gar in Serta County, Sichuan Province (est. 1980). A seated 120-centimeters height wax statue of Jigme Phuntsok is the most popular waxwork traded in Wuhouci. It can be ordered at the cost of 40,000–50,000 Yuan. A small version is about 10,000. These waxworks of Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok are made from already existing models that can be reproduced easily. The big, almost life-size waxworks usually ends up in monasteries and the small in private homes.

Like statues of Buddhas and deities that are made of metals, also the waxworks that I have had the chance to study come with hollow bodies. Being hollow, a ritual specialist can insert sacred ingredients and relics into the statue to consecrate it. Contemporary waxworks have bodies made of metals that are underdeveloped and hidden under clothing. Only the visible parts, which most often will be the head, the right arm, and the left hand, are made of synthetic materials such as rubber-like silicone for the flesh, resin for the eyes, and human hair for the head and body hairs. All statues that I have seen are seated in the lotus position, usually with both hands resting in the lap, perhaps one hand holding prayer beads. I have come across a couple of statues in more dynamic postures with active hand gestures (for instance, the demon-dispelling mudra).

The waxworks of Akhyuk Rinpoche and Artisan Jamyang Woeser

In the very back of a shop in Wuhouci sit two hyperrealistic wax statues dressed in Buddhist attire. Their careless placement tells us that this is not a sacred space, but then the assemblage is also not like the waxwork displays in a Madame Tussauds museum. The shop is owned by a Tibetan artisan monk named Jamyang Woeser, who used to be the attendant to Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok. I had visited this place several times over the years, and this is also where I first saw a Tibetan wax effigy in 2015 (the tertön mentioned previously). I have documented this waxwork in 2019 and 2020, and here I will describe what it looked like in January 2020 during my last visit.

The waxwork sits on an elevated linoleum plateau two stairs up. On the uppermost stair is a censer to the left, from where a sweet waft of incense arises – as is usual in Buddhist practice places. To the right is a donation box overflowing with bills, mostly one-Yuan bills but also fives and tens. Scattered around are hundred-Yuan bills and stacks of well-groomed one-Yuan bills collected with a rubber band. The stairs with the censer and the money offerings isolate the waxwork space from that of the customers and the goods with price tags, and visitors do not trespass beyond it.

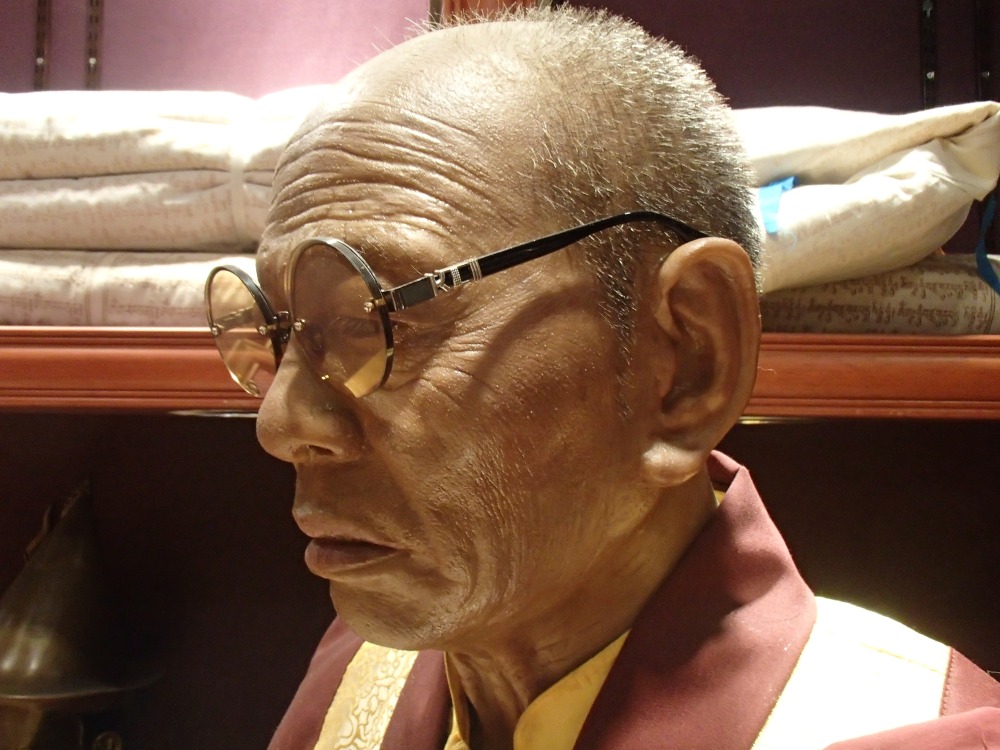

Figure 5: Wax model of the renowned Akhyuk Rinpoche. Photo by Trine Brox, 2020.

In the midst of big statues crowding this end of the room is a wax model of an elderly Buddhist monk. He looks small and frail, yet he is slightly taller than the average person. The wax model is of Akhyuk Rinpoche (1927-2011). He was one of Tibet’s most renowned meditation masters and a pioneer in the revival of Tibetan Buddhism after the Cultural Revolution. He founded in 1980 one of the largest monastic encampments known as Yachen Gar in Pelyul County, Kham (in Sichuan, the same province as the city of Chengdu, where Wuhouci is). Wax Akhyuk Rinpoche is seated and draped in monk’s robes that conceal everything but his hands resting on his knees. Someone has laid a yellow ceremonial scarf across his lap. His gaze is low, and one can hardly see the eyes behind his spectacles. Akhyuk Rinpoche’s face is dark and wrinkled, and his mouth rests seriously. There is no glow of life in his skin. He is an elderly man, and the statue also looks old. Perhaps it is true that this statue is ten years old, as the shopkeeper tells me.

The statue of Akhyuk Rinpoche had been ordered by a client whom the workshop had lost contact with. Believing that he had passed away, they had moved the wax effigy from the workshop to the shop for storage. Now, the statue was sitting there, serving no particular purpose. Nothing was done to prevent the degradation of the material, but they had taken measures to protect the statue from “harmful spirits” by writing the sacred syllables Om Ah Hum on the statue’s crown, throat, and heart centers. In that way, they wanted to prevent an evil spirit from moving into the statue’s empty body. Here, stored and displayed in the back of a shop, it was a commodity, the shopkeeper said, but some Tibetans nonetheless treated it as a pilgrimage site. That explained all the money offerings in front of wax Akhyuk Rinpoche.

There is also a second statue tucked away in the right-hand corner. This is the statue of a middle-aged man, also dressed as a monk. He looks happy and lively, playful, energized. Also he is seated. His right hand appears to be handling prayer beads, but there is none. His left hand rests flat open in his lap. A ceremonial scarf has been draped over his lap and arms. The placement of this statue is conspicuous. He is like an invisible force – someone who is hiding in the background but who orchestrates all this. In a way, that was also true. The wax model was of Jamyang Woeser, who is the artisan monk and boss of the enterprise. He is still alive and well, the shopkeeper answered, and praised him as a Tibetan pioneer and a true artisan, a lha bzo, a sculptor of receptacles for the divine. Jamyang Woeser produced wax statues for monasteries in Kham so that the people of Kham could “feel closer” to their lamas, he related. A Tibetan man walked into the store and was drawn to the waxwork in the back. He looked at Akhyuk Rinpoche approvingly and gestured with his hand that he respected it. Yet he could not get his head around who the monk to his right was.

The living and the dead

The idea of making wax copies of living Tibetans puzzled me – yet that is exactly what Madame Tussauds museums have popularized. So why was it strange in this Tibetan Buddhist context? Jamyang Woeser had not only “immortalized” himself in wax but also other contemporary Buddhist authorities. He had, for instance, made a wax statue of a Buddhist master who was still alive but had traveled to India. He was so dearly missed by his Khampa followers, so they collected money to purchase a human-sized wax statue of him to have in the local temple. The monk artisan has made many such statues but mostly of deceased Buddhist monks.

The Han Chinese wax sculptor, Mr. Li, thought that Tibetan temples wanted statues of their departed masters in wax because they look so realistic and lively: “They really want their master (shifu) alive.” Seeing him every day would make their devotion to him even stronger, and it would be as if he was still among them. They have such a strong attachment to their master, and the wax copy makes it possible to look at him every day, Mr. Li explained. Waxworks are affective because they resemble real persons with whom devotees connect spiritually, emotionally, and religiously. In that sense, wax is a new media for the replacement, preservation, or extension of the presence of the revered master. Wax makes the departed present here and now albeit he is living abroad or is deceased. The wax double of Jamyang Woeser situated in his store, his apprentice suggested, was like taking a photograph, or it was like those celebrities who had their images displayed in wax.

In the presence of statues

Some Buddhist material objects can be directly tied to the Buddha’s body, speech, and mind. Objects of the Buddha’s body include images and painted scrolls, speech are books and mantras, and mind comprises reliquaries and votive images. These objects are consecrated (Tib.: rab gnas, Chi.: kaiguang), which are rituals performed by ritual specialists to sacralize objects. Underneath both wax and metal statues is an opening into the interior of the statue. A ritual specialist will fill the body of the statue with sacred ingredients following ritual protocol.

Traditional Tibetan Buddhist statues materialize and personify concepts and ideals such as compassion, wisdom, good health, longevity, and prosperity. They come in different shapes: Wrathful and pot-bellied protectors stomping upon their enemies; serene-looking and bejeweled meditators revealing transcendental eyes in their palms and forehead; and multi-armed, genderqueer saviors who look at us compassionately. Their authenticity rests in a craftsmanship that includes iconographic correctness and proper engagement through body, mind, and speech. The authenticity of the wax statue, however, rests upon its resemblance and its ability to look human and alive. It is the wax statue’s sparkling eyes and recognizable features that ultimately proves his humanity and impermanence in the form of, for example, aging: It is among others his gray hair, heavy eyelids, liver spots, wrinkles, and reclining hairline that make the wax statue of Akhyuk Rinpoche authentic. That is on display in the Wuhouci showroom.

Why the client chose to have the old version of Akhyuk Rinpoche made in wax is interesting. The client could have chosen to preserve and remember a younger examplar. This waxwork had fixed Akhyuk Rinpoche in a late stage of his life when his eyelids were heavy, his gaze low and tired, his body frail and shrunken. That was how the client wanted to remember him. In contrast, the traditional statues depicting the Buddha, deities, or Buddhist masters are not displaying aging bodies, but ageless concepts, paths, and ideals. They are recognizable by their body postures, mudras, and props like begging bowls, lotus flowers, crowns, and multiple eyes and arms that promise compassion, wisdom, healing, longevity, and prosperity. Believers see compassion in the Avalokitesvara, good health in the Medicine Buddha, and longevity in the Amitabha. So what are the adherents of Akhyuk Rinpoche seeing in his wax effigy? And how does the statue of the living artisan fit in?

By Trine Brox

University of Copenhagen

NOTA BENE!

Acknowledgments are due to Tseringtso and Heng Peng, who worked as my very capable research assistants in Chengdu. Thank you so much for your company and help in 2020 and 2019, respectively.

Research into Tibetan waxworks is an ongoing side-project that I have not yet had the opportunity to discuss with colleagues. I do not know of any other research in Buddhist Studies or Tibetan Studies exploring the religious materiality of waxworks. I hope this work in progress can spark discussions and collaborations regarding Buddhist and Tibetan waxworks and its possible cultural precursors. I welcome discussions here on the blog by writing your comment below or by contacting me via Twitter @BroxTrine and e-mail: trinebrox @ hum.ku.dk

References

Ballestriero, Roberta. 2009. “Anatomical Models and Wax Venuses: Art Masterpieces or Scientific Craft Works?” Journal of Anatomy: 223-234.

Bloom, Michelle E. 2003. Waxworks: A Cultural Obsession. University Of Minnesota Press.

Kornmeier, Uta. 2008. “Almost Alive: The Spectacle of Verisimilitude in Madame Tussaud’s Waxworks.” In Ephemeral Bodies: Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure, edited by Roberta Panzanelli, 67-81. Getty Publications.

Napolitano, Valentina. 2017. “On Bone Relic Assemblages.” Material Religion 13 (4): 524-26.

Panzanelli, Roberta. 2008. “Introduction: The Body in Wax, the Body of Wax.” In Ephemeral Bodies: Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure, 1-11. Getty Publications.

Wallace, Elizabeth Kowaleski. 2014. “Recycling the Sacred: The Wax Votive Object and the Eighteenth-Century Wax Baby Doll.” In The Afterlife of Used Things: Recycling in the Long Eighteenth Century, edited by Ariane Fennetaux, Amélie Junqua and Sophie Vasset, 152-165. Routledge.